I lived in Beirut for over two years starting in 2012, where I worked on grassroots empowerment initiatives with a Lebanese and Syrian NGO. Media is a central part of life in Beirut, and Lebanese have a complicated obsession with their media. TV and radio relentlessly blast the insults being hurled among do-nothing politicians. My Lebanese friends and taxi drivers were always complaining about the constant bickering in the news without any progress in government and service provision. My experience with Lebanese media reflects the ongoing, motionless dance in which the Lebanese try to write off the government, but can’t help but stay tuned into the news for some impossible chance for change.

All of the main Lebanese TV stations and newspapers are directly linked to the country’s political parties and sectarian factions. This entrenchment has perpetuated the effects of the civil war–which officially ended in 1990–concretizing opposing national narratives within different sectors of Lebanon’s diverse society and prolonging and exacerbating political and sectarian rivalries and violence. Politicians take advantage of these outlets to point fingers and evade blame, and they use rhetoric and discourse that instills fear and perpetuates violence. More often than not, the main media outlets in Lebanon serve less to inform their citizens or improve governance than to provide entertainment, increase frustration, and produce apathy. Traditional media further calcifies Lebanese disillusionment in democracy.

The pro-Saudi Lebanese daily newspaper owned by the Hariri family, al-Mustaqbal, features a permanent picture of assassinated Prime Minister Rafik Hariri.

Still, Lebanon–I should say, Beirut–boasts an animated media sector relative to its Middle East counterparts, thanks in part to government neglect. In Beirut, where every religious community and political grouping live side by side, the news is always being debated in the streets, offices, and cafes. In contrast to many other countries in the region that I visited during my time in Lebanon, in which governments exert control over political messages and narratives, Lebanese media allows for some public disagreement and exposure to a culture of diversity of opinion. Of course, this culture of diversity is accompanied by sub-cultures of control, intimidation, and censorship within each of these media outlets and political groupings, restricting internal dissent in traditional media.

Relatively unrestricted access to media also means that Beirutis are informed about regional and world politics and trends. I quickly determined that the Lebanese are among the most informed populations I have ever met when it comes to international news. There were few shared taxi rides, called “serveece,” in which the driver wasn’t opining about Obama’s latest remarks or Bush’s legacy. It is my belief that access to the Internet allows Lebanese to stay embedded in the world and stimulates some level of citizen engagement despite the constant reminder that the government is entrenched and unresponsive to citizen needs.

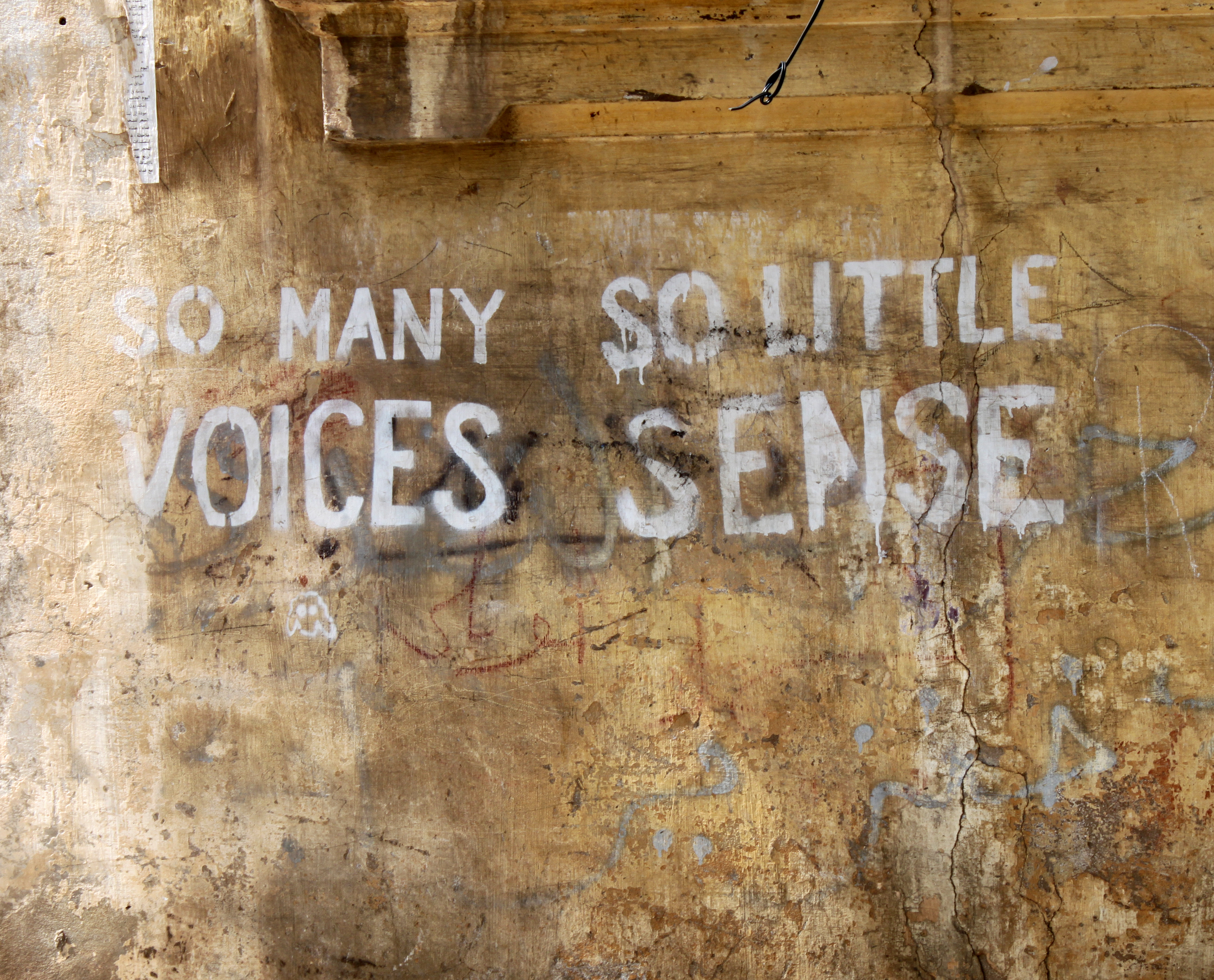

Where traditional media has failed to hold the government accountable and highlight issues important to average Lebanese, alternative and independent media outlets have taken on the challenge—even in spite of huge risks. Through websites, social media, digital documentation technologies, and even graffiti, activists and independent and freelance journalists produce analysis and report on local and special interest stories that mainstream media outlets ignore. Notable blogs include the Beirut Report, Beirut Syndrome, Gino’s blog, Beirut Spring, Blog Baladi, ShiaWatch, and Qifa Nabki. Many of these outlets use satire and comedy to criticize their representatives. In fact, even some of the main TV stations are able to take on more controversial issues and highlight dissenting views through comedic, satirical, and non-news media programming.

“You stink” activists used drone technology to highlight trash collection issues in Lebanon ignored by mainstream media and politicians.

Unfortunately, the few advantages of the Beirut media landscape that I experienced living there don’t reach beyond the capital. Whenever I left the city, I was reminded of the fact that media in Lebanon is extremely Beirut-centric. I perceived a deep divide between Beirut and the rural, disconnected parts of Lebanon. The frenzied hubbub in Beirut and its media does not translate to rural parts of Lebanon, in the Bekaa, the north, and the south.

This disconnection is emblematic of a larger governance issue. The dismal telecommunication system and service delivery problems outside of Beirut mean that the periphery lacks access to electricity, Internet, and mobile technologies, making it particularly difficult to tune into TV news programs or follow alternative and social media. The infrastructure problems physically disconnect rural areas from the capitol and, therefore, from national debates. The local needs of these populations have long been ignored by the government and both traditional and alternative media don’t focus attention on them.

Few community radio channels exist in these areas. Radio channels sponsored by political parties provide these communities with a partisan connection to the news and politics. For example, while Beirut-based Free Lebanon Radio broadcasts to rural areas and deals with local issues, it is sponsored by the militia-turned-political party, Lebanese Forces. The continuation of the urban-rural divide in Lebanon’s media represents an oversight on the part of alternative media outlets based in Beirut. While this is no doubt a function of few resources for production, new media should still reach out to youth outside of main cities to bolster their efforts to change the media’s status quo in Lebanon.

As we watch the media, like most other institutions, melt down in Lebanon with historical newspapers shutting down and downsizing, it is clear that there is little buy-in for traditional media there. Considering independent media’s tenuous position and limited audience in urban areas, we can only hope that these newer outlets are able to grow and find support, both financial and technical. If these outlets are able to address the concerns of all Lebanese–not just urban populations–and use creative ways to reach communities in areas hard to access, they could be the basis for a more engaging and inclusive media sector and ultimately a more active and integrated citizenship in Lebanon.

Madeleine Stokes is the Assistant Research and Outreach Officer with the Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA) at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Prior to joining CIMA, Maddy worked on NED’s Middle East and North Africa program team. From 2012 to 2014, she worked on democracy-building approaches and NGO management in Beirut, Lebanon. There she supported local initiatives to empower civilians in Lebanon and Syria. She developed and oversaw programs that advocated for women and independent voices and contributed to research and public polling efforts that highlighted the deleterious effects of political conflict on local communities and democracy.

Comments (0)

Comments are closed for this post.